Analysis of Lermontov's poems

- Poetry analysis

- Lermontov

- Angel

- Gratitude

- In a difficult moment of life

- Valerik

- Spring

- I go out onto the road

- Mountain peaks

- Thought

- There are meanings to speeches

- Will

- Star

- And boring and sad

- From under a mysterious, cold half mask

- Caucasus

- How often surrounded by a motley crowd

- Dagger

- When the yellowing field is agitated

- leaf

- My demon

- Prayer I am the mother of God

- Mtsyri

- In the wild north

- No I'm not Byron I'm different

- Beggar

- Loneliness

- She is not proud of her beauty

- Autumn

- Sail

- Captured knight

- Poet

- Prediction

- Prophet

- Goodbye unwashed Russia

- We parted but your portrait

- Motherland

- Death of poet

- Dream

- Neighbour

- Stanzas

- Three palm trees

- Clouds

- Heavenly clouds, eternal wanderers

- Prisoner

- Cliff

- I want to live, I want sadness

- I will not humiliate myself in front of you

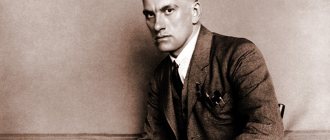

The works of the famous poet of the first half of the 19th century are popular not only in the Russian Federation, but also abroad. 3 centuries have passed since the poet passed away. His comrades and relatives, as well as writers with whom he closely communicated, have long been dead. But his brilliant works make us plunge into the world of culture and real poetry.

Mikhail developed the basic inclinations for writing when he was a teenager. It was in the family that disagreements arose between the father and grandmother of the young genius. If Yuri Petrovich recognized Misha as a talented child, then Elizaveta Alekseevna wanted her grandson to look after the old lady. But, all the same, while studying at the boarding school, the young man was already published in local publishing houses. The very first poems appeared in 1829 in Moscow. They talked about the Fatherland, friendship and the high purpose of the poet.

Soon Mikhail Yuryevich became close to the Decembrists. He wrote down their thoughts and conversations in a notebook, after which he reflected all these worries in his poems “Prophet” and “Motherland”.

In 1830, “Prediction” appeared, which talks about the Pugachev uprising, and a little later the novel “Vadim” was written, which remained unfinished.

At the age of 20, the young man becomes a military serviceman. He still had the theme of struggle and exploits in his thoughts. In 1837, Borodino was born, dedicated to the 25th anniversary of the Battle of Borodino. And now, when we reread these brilliant lines again, the victorious heroes of the last century stand before us. Lermontov wanted with all his heart to show the poem to Pushkin, but he died in a duel. The tragic death alarmed him so much that he immediately dedicated the delightful poem “The Death of a Poet” to his mentor.

On duty, while staying in the Caucasus, Lermontov completed work on “The Song about Tsar Ivan Vasilyevich, the young guardsman and the daring merchant Kalashnikov.” The censors for a long time did not want to publish this work, but V.A. Zhukovsky was delighted with what was written and asked for this creation to be published.

Here “Hero of Our Time” was created, “Demon” was rewritten many times, and the poem “Mtsyri” was created in one breath. All the character’s thoughts and dreams were similar to the views of many people, so these works were reread several times. After some time, another poem, “The Fugitive,” appears, which denounced betrayal.

During the next exile to the Caucasus in 1840, the book “Poems of M.Yu. Lermontov” was published in St. Petersburg. The publication was a huge success among readers.

In 1841, “Motherland” was published in the magazine, where the author describes the suffering of the Russian people. The freedom-loving poet is not in St. Petersburg for long, as he is asked to leave the city. It was hard for him to part with his friends. And in his latest creations “Oak Leaf”, “Cliff”, a lot of anxiety and sadness can be traced. Lermontov died on July 15, 1841, but his poetry and prose are still valued by the reading public.

Brief biography of the poet

Mikhail Yuryevich was born in October 1814 in Moscow. The young poet was raised by his grandmother. Therefore, the poet’s childhood years were spent in the Penza province in the Tarkhany estate. He received his first education at home. Next, the young man continues his studies at the university boarding school, which is located in Moscow. There the author begins to write his first works.

Later, the young man enters Moscow University, where he is very fascinated by the works of Schiller, Byron and Shakespeare. After graduating from the university, Mikhail Yuryevich studied at the warrant officer school located in St. Petersburg.

Since 1834 he has been serving in the hussar regiment.

The poet gains his fame thanks to his scandalous work “The Death of a Poet,” which he wrote in memory of Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin. This poem was the reason for his first exile.

Spending time in exile in the Caucasus, he further realizes his potential as a poet. With the help of his grandmother, who managed to come to an agreement, he is returned to St. Petersburg, where he is successfully reinstated into service. But, after some time, the poet enters into a duel with E. Barant, who was the son of the French ambassador. This duel turned out to be a new exile for Mikhail Yuryevich to the Caucasus, where he had to take part in hostilities. The poet died at the moment when he was returning from his second exile at the hands of Martynov, with whom he fought a duel.

Means of expression

of epithets makes the language of the poetic text figurative and lively : “foggy mountains”, “forgotten dust”, “rusty sword”, “brave fighters”, “alien snows”. These linguistic means of expression are the most favorite in the poet’s work. Romantic paintings from distant years seem to come to life thanks to the artist’s skill.

The poem is full of anaphors , this gives it musicality and emotionality (first stanza, 1st and 3rd verses: “Why am I not a bird, not a steppe raven...Why can’t I soar in the skies.” Second stanza, 2nd and 3rd verse: “Where the fields of my ancestors bloom, Where in the empty castle, on the misty mountains...”).

Previous

Analysis of the poems “Autumn Evening” analysis of Tyutchev’s poem according to the plan briefly - idea, history of creation, lyrical hero

Next

Analysis of poems “Testament” analysis of Lermontov’s poem according to the plan briefly - artistic techniques, theme, idea

Genre, direction, size

Genre of the work by M.Yu. Lermontov “The Beggar” is a lyrical poem. It is worth noting that it contains elements of elegy, as it contains motifs of unhappy love, disappointment and loneliness.

Direction of creativity M.Yu. Lermontov - romanticism. The lyrical hero suffers from unrequited love and loneliness; he is a tramp, despised by society.

The meter of the poem is iambic tetrameter. This is a two-syllable poetic meter; unlike trochee, the stress falls on the second syllable. The writer also uses simple cross rhyme.

History of creation

The poem was written by young Lermontov in 1831 on July 29 in the Serednikovo estate. The poet's family kept the legend that their family descended from the Scottish bard Thomas Learmont. How reliable this information is is unknown, but the young man’s imagination filled in all the missing details, and a slightly naive, romantic poem “Desire” appeared.

The young man’s dreams of freedom, the opportunity to visit the distant country of his supposed ancestors were obviously unrealistic, this was due to the time and financial situation of the poet’s family. Only very wealthy people could afford such a trip. The sixteen-year-old boy understood this perfectly, and his desires were realized in a beautiful, sad poem with an appropriate title. The young man’s passion for history and foreign literature also played a role. Also, one should not exclude the influence of the famous romantic poet D. G. Byron, whose work young Lermontov was captivated by during this period. The poem was first published in the journal Otechestvennye zapiski in 1859.

Composition

Composition - the poem consists of six stanzas with paired rhymes. In each quatrain, the 1st and 3rd stanzas are written in amphibrachium, the 2nd and 4th in anapest. This gives the poetic text a very unique sound, which is rather unusual for most of Lermontov’s works. The first four stanzas are the imaginary journey of the lyrical hero, reincarnated as a “steppe raven.”

The last two stanzas are an exclamation about the inevitability of obeying one’s fate, the impossibility of changing what is destined.

Lermontov in Russian literature. Problems of poetics

Lermontov and Russian poetry

(instead of introduction)

Researchers noted that Lermontov was perhaps the first major Russian poet in whose work antiquity almost completely disappeared, and not only as a pan-European arsenal of poetic imagery, but also as a cultural tradition, a measure on which European art was habitually oriented for several centuries .

This observation is significant: Lermontov is the heir to the Pushkin era, as if starting directly from the point to which Pushkin brought our poetry. It expresses the new position of literature, characteristic of the 19th century.

Pushkin constantly correlates all life phenomena that came into the sphere of his attention with the experience of world culture: a picture of everyday estate life - “the Flemish school of motley litter”; the description of the statue by a Russian sculptor is traced back to antiquity by the very form of the verse and its distinct genre tradition; An anecdote from local life is compared with a textbook episode of ancient history (“Count Nulin”). Constant comparisons and cultural associations, sometimes humorous, sometimes serious, but always deep in meaning, overwhelm Pushkin’s works. Stylizations, translations and imitations, original creations that take European life as material - all this is a kind of cultural trade, and at the same time - a polemical device necessary for the aestheticization of national life, proof of the fundamental suitability for literature of any life material, the equality of everything in the face of poetry. Pushkin proved this, and his successor Lermontov was freed from such a task.

If before Pushkin (and in many ways also for him) new literature was, as it were, an organ for the development of world cultural heritage, culture in general - this is what it is directed towards and thereby enriches national life - then, starting with Lermontov, poetry is addressed directly to the processing of life impressions, no mediation between soul and life. In this respect, Lermontov is more democratic than his predecessors and is closer to the commoners. Against the background of great commonality with Pushkin (cf. the impression of Lermontov’s poetry by the writers of Pushkin’s circle), Lermontov’s absence of these, relatively speaking, “translational” cultural colors is noticeable and meaningfully important.

The almost unexplored problem “Lermontov and Russian poetry of the 18th century.” although it can be placed, it is unlikely that any direct contacts will be found here. Indirectly - through the civil lyricism of the Decembrists and Pushkin - Lermontov (his, in the words of B.M. Eikhenbaum, “oratorical lyricism”) is connected with the odic tradition of Russian classicism, through elegy - with sentimentalism (only in the earliest period - see “Autumn” , "Tsevnitsa").

Lermontov's poetry is the fruit of the 19th century, when in the works of the great Russian poets of the first third of the century - Zhukovsky, Griboedov, Pushkin - the European cultural tradition, instilled by Peter's reforms, became fused with the national element, when a new man, a Russian man of European consciousness, found a language and a voice in literature.

Like all poets of the first half of the 19th century who entered the literature after Pushkin, the problem of the relationship between his poetic system and Pushkin’s was acute for Lermontov. With an invariably positive general attitude towards Pushkin’s legacy, Lermontov went through different stages of his creative development - from direct imitation and apprenticeship in youthful poems (“Circassians”, “Two Slaves”, “Prisoner of the Caucasus”) to ideological polemics (“Three Palms”, “ Prophet") and complex artistic self-determination in relation to the Pushkin canon. At the same time, authoritative researchers of Lermontov’s work (V.V. Vinogradov, D.E. Maksimov, A.N. Sokolov, U.R. Fokht) associate the emergence of a new stylistic trend in Lermontov’s late lyrics, characterized by a large simplicity and clarity, the development of conversational intonation and the inclusion of prosaisms in the high poetic structure of thought (“Valerick”, “Testament”, “Motherland”). However, the connection of these poems with Pushkin’s tradition should be understood in the most general terms - the originality of Lermontov’s poetic intonation here is absolutely indisputable.

Pushkin's poetry is the mastery and habituation of speech and speaking by verse. Everything became worthy of poetry and accessible to it. Pushkin's poetry is a powerful flow of speech, the rapid conquest and subordination of ever new areas and spheres of life to verse. In this regard, Lermontov’s early lyrics, with their kind of “close verbosity,” sometimes thoughtful, sometimes pathetic, are a direct follow to Pushkin, a continuation of the same trend of a kind of expansion of poetic speech. The principle of late Lermontov's lyrics is different. Here begins the rejection of the understanding of poetry as a stream that captures and draws in the entire surrounding world, and poetry is established as a series of flashes, as a fixation of an instant poetic experience. Lermontov refuses to try to develop and continue this experience. In the ongoing poetic tension, in the large verse mass, he seems to see the danger of falling into artificiality. Lermontov's reflection from the purely ideological sphere extends to the artistic. The inertia of the Pushkin canon, which became common place in the poetic culture of the 30s, begins to be overcome. XIX century and in the hands of imitators the danger of irresponsible rhetoric actually lurks. This is Lermontov’s radical poetic innovation.

Along with the Pushkin tradition, it is necessary to note two more that had serious significance for Lermontov.

The first is the poetry of the Decembrists. Her influence, along with that of Pushkin and Byron, is felt in Lermontov's early poems (see "The Last Son of Liberty"). On the other hand, Lermontov and some of his contemporaries (in particular, Slavophile poets) continued the traditions of Decembrist civil lyrics. The Decembrists created oratorical poetry, which uniquely refracted the traditions of high lyricism of classicism, deeply transformed by their romantic poetics, but it was in their poems that they continued in the 19th century. live the intonation of the solemn iambic. In his lyrical poems, Lermontov often uses “odic” iambs, which are also found in Pushkin, but are especially characteristic of the Decembrists (“The Death of a Poet,” “Duma,” “Don’t Trust Yourself”).

The poetic canon of “high” poems on a civil theme developed by Russian romantics throughout the 19th century. remained a kind of standard, a form in which several generations of Russian lyricists sought to express their credo. These poems express the views and feelings of people of different beliefs and different eras. And yet, these poems are somehow surprisingly similar to each other, stable in their general outlines, similar in intonation: “Citizen” by Ryleev, “Liberty” and “Village” by Pushkin, “Duma” and “Poet” by Lermontov, both poems “Russia” by Khomyakov, “Motherland” and “In Memory of Dobrolyubov” by Nekrasov, “Like a dear daughter to the slaughter” by Tyutchev, “Scythians” by Blok.

Finally, his impression of Zhukovsky’s poetry was undeniably important in Lermontov’s work.

The romantic worldview was historically most acutely expressed in the ballad and romantic poem. As already mentioned, among the Russian predecessors, the Decembrists and Pushkin had the greatest influence on Lermontov’s poetic work. The ballad in Russian literature is firmly associated with the name of Zhukovsky. The meaning and place of the ballad in Lermontov’s work cannot be understood if we limit ourselves to considering the canonical examples of the genre (there are few of them, and they are of a student or primitive nature), but the influence of the ballad, its problematics, “color” and poetics is very noticeable in Lermontov’s lyrics. The most characteristic motif of the ballad - the motif of fate, a person’s collision with fate, or the manifestation of power over people by some higher forces - is clearly close to Lermontov’s poetry, as is the inherent focus on the fate of the individual in the ballad, the refraction of philosophical, moral and socio-historical issues through it. The constructive features characteristic of the ballad—intense drama, a sharp conflict between characters, usually leading to a tragic outcome, an element of exoticism, a flavor of mystery—are akin to Lermontov’s artistic system. At the same time, at the time of Lermontov’s mature creativity, the ballad genre was largely exhausted. Lermontov artistically overcomes the inertia of the genre canon: the analytical moment intensifies, the lyricism of the ballad increases, the author himself seems to strive to become its hero. Hence the ballad nature of Lermontov’s lyrical world as a whole and the erosion and transformation of the ballad canon. A connection with the ballad tradition is also revealed by the quality of verse in Lermontov’s late lyrics. (This will be discussed in more detail in the chapter “The Influence of the Ballad on Lermontov’s Late Lyrics”).

Despite all his closeness to his great predecessors, and above all to Pushkin, Lermontov, as a bright exponent of the consciousness of the Russian intelligentsia of the 1830s, turned out to be, in the famous expression of Belinsky, a poet of “a completely different era.” Beginning an article about Lermontov's poems with a heartfelt and highly artistic characterization of the pathos of Lermontov and Pushkin's poetry, Belinsky accurately expressed the reader's impression of Lermontov's poetry as more dramatic, acutely conflicting, full of reflection and tragic contrasts between intense criticism, enormous spiritual activity and the consciousness of the practical powerlessness of modern man. Lermontov's youthful romantic maximalism turned out to be surprisingly adequate to the crisis era of Russian thought and colored all of his work. Although in recent years it has far from exhausted the character of his lyrics, this color turned out to be, so to speak, the most catchy, noticeable, so much so that in the minds of a person of Russian culture, such forced drama, intense conflict in poetry is perceived precisely as Lermontov’s tradition, Lermontov’s line in literature.

Lermontov's literary era was a period of summing up the results in Russian and European romanticism, while at the same time a new “great style” was emerging in literature - realism. All this, however, does not exclude the possibility of qualitative development and enrichment of romanticism. About this period we can say: the relevance of the affirmation of romanticism as a method has been exhausted, but the method itself has not yet exhausted its capabilities.

The predominant part of Lermontov's artistic heritage is associated with the intra-romantic evolution of the poet. Comparison of Lermontov's lyrics with the main trends of romanticism of the 30s. shows that not only ideologically, but also in the sphere of artistic tasks, Lermontov expressed the progressive tendencies of literary development precisely in the form most characteristic of the time. If Pushkin is from the romanticism of the 20s. in the 30s moves to the creation of a realistic system, then all Russian literature is characterized by a slightly different path: through a new stage of romanticism, emerging in the 30s. The highest expression of precisely this line of literary development was the work of Lermontov.

Romanticism of the 30s. differs from pre-December romanticism in the strengthening of the analytical moment in the artistic knowledge of reality, the gradual formation of the principles of historicism when approaching modernity. However, the analysis is carried out in the form of subjective romantic reflection; historicism is still far from concrete and has an abstractly generalized nature. Romanticism of the 30s, as in the previous era, was not homogeneous; it included movements that differed from each other ideologically and had features in aesthetic theory, poetic principles, and the genre system.

A notable phenomenon in the literature of the 30s. became the poetry of so-called philosophical romanticism. The artistic searches of romantics of this type were a historically relevant phenomenon, since they reflected the interest in the philosophical problems of existence characteristic of the era. At the same time, their inherent idea that in poetry philosophical ideas can be expressed in a way of direct, immediate presentation (a mixture of scientific, philosophical and artistic thinking) alienated Lermontov and the other greatest lyricist of the era, focused on philosophical issues, Baratynsky, from them.

In the early period, Lermontov widely used the genres of philosophical monologue and romantic allegory, formed in the poetry of philosophical romanticism (Venevitinov, Shevyrev, K. Aksakov, Khomyakov). Based on the romantic allegory (“Cup of Life”), a new type of poem with a symbolic image (“Sail”, “Cliff”, “Clouds”) gradually takes shape in Lermontov’s poetry.

The philosophical monologue is one of the most common forms in Lermontov’s early lyrics. However, his monologue differs from this genre of philosophical romantics in its clearly expressed personal character. Lermontov strives not to express a thought (which is typical of poets of philosophical romanticism), but to convey reflection, that is, to convey a thought in its formation, development, with a clear imprint of the consciousness that gave birth to it (“1831 - June 11th”). Later, Lermontov does not apply this form in its pure form, however, using the experience of philosophical monologue in other genres. Of the entire group of philosophical romantics, Lermontov’s most enduring interest was attracted by Shevyrev and Khomyakov, the most brilliant poet of Slavophilism. A hidden dialogue with Khomyakov can also be traced in Lermontov’s later poems. At the same time, Khomyakov, in his most acutely journalistic poems, clearly experiences the influence of the civil poetry of the Decembrists and Lermontov. In general, the relationship between Lermontov and Khomyakov can be represented as follows: Lermontov’s attention and interest in Khomyakov, expressed in textual exchanges that do not have the nature of a semantic connection; mutual rapprochement in Lermontov's oratorical verses and Khomyakov's programmatic verses; in the late Lermontov there is a clear artistic repulsion from Khomyakov’s rhetorical programming (“Dispute”, “Motherland”).

The new quality of the genre in romanticism creates the fundamental possibility of the emergence of a romantic movement based on a kind of “expansion” of any lyrical genre. A special angle of view on the world, a sphere of artistic vision, characteristic of any genre, can become comprehensive for a lyricist, coincide with the author’s position in relation to life in general, and spread to other genres. In Russian romantic poetry this happened with elegy.

Despite the fact that the heyday of the elegy genre dates back to the 1810s - 1820s, we can talk about the special elegiac movement of romanticism specifically in relation to the poetry of the 30s. During this period, a special angle on the world, which is characteristic of elegy, for many poets begins to characterize their poetic system as a whole. The most remarkable poet associated with elegiac romanticism is Baratynsky, a recognized classic of Russian elegy and at the same time of Russian philosophical lyricism. What Baratynsky has in common with the poets of elegiac romanticism is a specially elegiac angle of view on the world, characteristic of all his lyrics, regardless of the genre of a particular poem. At the same time, in its problematics, Baratynsky’s poetry is close to the lyrics of philosophical romanticism. But the poet's aesthetic position was hostile to this trend of romanticism. This artistic antagonism was clear to the theorists of philosophical romanticism, which is why their attitude towards the “poet of thought” was very cold.

The intellectual in Baratynsky's poetry, like that of Lermontov, was deeply personal. A thought, an idea is emotionally experienced, and, moreover, in a historically specific consciousness. This attention to the feeling of the thinker reflected the experience of Baratynsky the elegiac. A special genre is being formed in his lyrics, which is a fusion of elegy with a philosophical monologue (“The Last Poet”, “What are you doing, days!”, “Autumn”).

The paths of Lermontov and Baratynsky to the creation of truly artistic philosophical lyrics coincided, since both of them, unlike the poets of philosophical romanticism, embodied the intellectual as deeply personal, created and experienced in the individual consciousness.

In Baratynsky’s late lyrics, a single image of an era and a person—a contemporary of the poet—appears. This allows us to talk about such a degree of concreteness of Baratynsky’s poetic world, which is comparable only to Lermontov’s.

Thus, one can see that the similarity between the lyrics of Lermontov and Baratynsky concerns the most essential aspects of their artistic system.

Elegiac romanticism was the broadest, most influential, and most ideologically diverse movement in romanticism in the 1930s. A connection with the poetics of elegiac romanticism undoubtedly exists in the lyrics of such writers as Polezhaev, A. Odoevsky and even Kuchelbecker, whose work, of course, cannot be completely attributed to the elegiac movement. This is a special phenomenon in poetry, on the one hand, associated with the traditions of Decembrist romanticism, as it had developed by 1825, and on the other hand, using the achievements of elegiac romanticism.

The discovery of Decembrist poetry was the genre of lyric-oratorical monologue, iambic poem on a civil theme, based on the odic tradition of the 18th century. This genre is developing intensively, in particular, in the poetry of Kuchelbecker, especially in the 30s. During this period, he was influenced by the so-called “iambs” (“Slanderer”), an ancient lyrical genre revived in modern poetry by Auguste Barbier.

Iambics are characterized by the development of a socially important topic in the form of an oratorical monologue, combining high civil pathos with satirical attacks and grotesque characteristics. This type of lyric-oratorical monologue is also developed by Lermontov, although it differs from classical iambs. Among the poems of the late period, “The Poet” and “Don’t Trust Yourself” come closest to the iambic genre. “Duma,” despite the fact that some of its lines, as noted in Lermontov studies, directly go back to Barbier, as a whole has a different genre nature: it has a strong connection with elegiac lyrics, which is characteristic of Russian romanticism of the 30s. In this respect, Lermontov’s oratorical lyrics are closest to similar poems by A. Odoevsky. Odoevsky’s elegy “Why are you sad, children of dreams,” which is an interweaving of philosophical meditation of an elegiac nature with a pathetic oratorical monologue, foreshadows Lermontov’s “Duma” in that in it the entire range of melancholic emotions usual for an elegy is illuminated by the desire to penetrate into the general meaning of one’s individual destiny, it expands to the scale of philosophical reflection on history, its laws, and its purpose.

Significant place in the romanticism of the 30s. belongs to Polezhaev, a poet of a new generation, not biographically connected with Decembrism. The most significant feature that brings Polezhaev’s lyrics closer to Lermontov’s is the development in it of the theme of a demonic hero, traditional for European romanticism. The demonic hero of Polezhaev is already similar to the heroes of Byron, since his consciousness is devoid of the completeness and versatility of negation, the grandeur of the critical spirit. However, he benefits from the social concreteness of his criticism. Lermontov's demonic hero has a greater intensity of spiritual quest than Polezhaev's hero. At the same time, Lermontov’s protest is broader and more consistent. In its classical form, the demonic hero belongs to Lermontov’s youthful poetry. In the poetry of the second stage, he enters only some aspects of his content into the broader image of the “hero of the time” (mainly this is the pathos of negation, which in Lermontov has a touch of romantic maximalism to the end).

The influence of Lermontov’s work on his contemporaries and the generation of poets closest to him manifests itself very early and goes along different lines.

In the poetry of the 40s and early 50s. XIX century The tradition of Lermontov's philosophical and oratorical iambic monologues was adopted to the greatest extent. Either pathetic or filled with reflection, the monologues of Ogarev, like Lermontov, who was the exponent of the sentiments of the advanced intelligentsia of the 30s and 40s, are under the noticeable influence of Lermontov’s lyrics. Lermontov's intonations are clearly noticeable in the poetry of Apollo Grigoriev (as you know, Belinsky noted this in his review of Grigoriev's collection).

The radical poetic innovation of the last period of Lermontov's work did not find a direct and immediate continuation among his contemporaries and immediate heirs. But objectively, the very conciseness of his late lyrics is akin to Tyutchev and Fet. We can say that all three poets are united by the culture of poetic miniature. And it goes back - especially in Lermontov and Fet - not to literary sources (traditional genres of poetic “little things”), but is born from the common understanding of poetry by these writers not as a lasting and developing tension, but as a recording of individual bright flashes of poetic experience.

If in the history of the romantic poem Lermontov was destined to write the last and brightest pages with “The Demon” and “Mtsyri”, to become the consummator of the tradition, then his so-called “stories in verse”, experiments in everyday poems, were further developed in the 40s and 50s. XIX century Here it is necessary first of all to recall Turgenev’s poems “Parasha”, “Andrey” and “Landowner”.

A fundamentally new stage in the fate of Lermontov’s poetry will come in the 50s and 60s. XIX century, and it is associated with the name of Nekrasov.

Immediately after Lermontov's death, his unpublished poems appeared in print. Since 1847, several collected works, previously considered complete, have been published one after another. During this period, Lermontov seemed to become an active participant in the literary process, and at the same time, he was already a classic, already history. His dramatic fate, the aura of a civic poet - all this focused the sympathetic attention of the progressive intelligentsia on his poetry. This is the reason for the influence of the poetic intonations of Lermontov’s oratorical poems on Nekrasov, who often directly traced his poems to Lermontov with the help of a subtitle, reminiscences or hidden quotes. This line of succession as a direct continuation is quite obvious. But Lermontov was not only the author of famous civil poems, but also the creator of famous melodies of Russian poetry, surprisingly unique in sound, such as “Leaf”, “On secular chains...”, “In a difficult moment of life”. They entered the consciousness of Russian readers, dissolved and spilled into our poetry, and became classics. Although this Lermontov influence was more latent, not as obvious as the echoes of his poetic declarations, it turned out to be hardly less important and fruitful. It was precisely the rhythmic and melodic expressiveness and originality of Lermontov’s verse that was one of the reasons that Lermontov’s poetry turned out to be the most popular material for so-called rehashes. A satirical or humorous narrative, superimposed on a well-known and popular rhythmic and intonation pattern, evoking the most poetic classical lines, was especially effective in reducing the ridiculed phenomenon.

The general intense polemical nature of Nekrasov’s poetics noted by Eikhenbaum, as well as the important role of the feuilleton, journalistic principle in the originality of Nekrasov’s poetic voice, were the reason for the special type of his connection with the Lermontov tradition. In Nekrasov’s attitude towards Lermontov, there was also this specific shade: a parodist-imitator to the original, to the object of parody, a purely professional understanding by the poet-journalist of what kind of grateful material this or that popular melody gives into his hands. We see such a course of poetic processing of Lermontov’s melodies both in the “Lullaby” and in “The Writers” from “Songs about Free Speech”, where a direct link to the original source is given. We find even more rehashes in Nekrasov in a hidden form.

Finally, it must be said that Nekrasov continues the development of three-syllable poetic meters begun by Zhukovsky and developed by Lermontov. Compared with his predecessors, Lermontov significantly expanded the scope of use of three-syllable meters; in his later lyrics they were no longer necessarily associated with “exotic” subjects, still retaining a subtle flavor of “balladry”. Nekrasov finally masters three-syllables as the author’s personal intonation: it is with three-syllables that all readers—both the poet’s contemporaries and us—are associated with the idea of a special, unique Nekrasov voice.

Nekrasov's line is usually distinguished by its characteristic elongation, which is achieved by the use of dactylic endings to the verse. According to the observation of I.N. Rozanov, it was Lermontov who approved such an ending in Russian poetry.

Since already in the middle of the 19th century. Lermontov firmly took his place among the classics, together with Pushkin he was perceived as the founder of new poetry, his influence on writers of subsequent generations became widespread and at the same time quite heterogeneous. This is very noticeable already in the 1870-1880s, when Lermontov’s tradition acquires a tendency to “erosion”, to transform from Lermontov’s own into a general cultural, general poetic one. This is largely due to the fact that, as in the 40s, the type of iambic oratorical monologue, often having the character of an invective, is used to the greatest extent, that is, a type that, as we have already said, with all the perfection of Lermontov’s works of this kind nevertheless, it was not a specifically Lermontov discovery: it was with these verses that the poet himself was included in the literary tradition. This tradition is perceived as Lermontov's by readers of civilian poets of the 70s and 80s. XIX century (Pleshcheev, Yakubovich, etc.) because the name of Lermontov was firmly associated with the idea of poetry of negation, with increased conflict and drama.

On the other hand, the “timelessness” of the 1880s. updated the motives of reflection, longing for heroism that had disappeared from historical reality, motives of self-condemnation, which also traced their lineage to Lermontov. However, among the eighties, this theme lost its courageous flavor, lost the energy of denial inherent in Lermontov’s poems, the shade of moral stoicism characteristic of Lermontov, now it often sounded with notes of repentance (Apukhtin, Nadson).

Sluchevsky’s sarcasms are perceived as a development of other aspects of Lermontov’s lyrics (motives of “bitterness and anger,” irony).

Lermontov's rhythmic and melodic achievements in this era continued to serve as the basis for “rehash” in satirical poetry.

Lermontov's melodic diversity and rhythmic innovation influenced the poets of the decadent circle to a much greater extent. Declaring the defense of poetry as an art, striving to revive the culture of verse, which really fell into decline in the Epigonian post-Nekrasov era, the Symbolists could not help but experience the influence of Lermontov. At the same time, many of them denied the significance of Lermontov’s tradition for modernity (Balmont, Minsky), while others sought to give a mystical interpretation of the content and general meaning of Lermontov’s work (Merezhkovsky).

In addition to Lermontov’s poetic achievements, Lermontov’s rich poetic symbolism apparently had an undeniable influence on the Symbolists’ lyrics. The very type of poem with a symbolic image was approved by Lermontov. However, in the artistic system of symbolism it has shifted: if for Lermontov the symbolic image was an expression of a poetic generalization of the philosophical meaning of certain life phenomena, then for the symbolists it becomes a sign of “other worlds”.

Among all the Symbolists, Blok undoubtedly had the deepest contacts with the poetic world of Lermontov. The significance of Lermontov’s poetry for Blok was great, and it cannot always be fully grasped based only on direct textual “reflections”: “the spiritual image of Lermontov passed through Blok’s entire creative life” (D. Maksimov). In addition to meaningful connections - convergences and divergences with Lermontov’s thoughts on life, with his concept of the world (they are traced in D.E. Maksimov’s article “Lermontov and Blok”) - apparently significant is the feeling of the internal kinship of their poetic systems. Constant lyrical tension, which in the minds of readers of the 19th century. perceived as the “Lermontov beginning” in our literature, is highly inherent in Blok’s poetry. Unlike Lermontov, Blok even had the character of a somewhat conscious attitude: symbolism, after all, was characterized by the desire to extrapolate lyrical experience, to aestheticize life as a whole. With the crisis of the symbolist worldview, this type of lyrical experience in Blok, it seems, did not change - it was an organic property of his poetic gift.

In the 20th century The tendency to assimilate Lermontov’s poetic tradition as a general cultural, general poetic tradition continues and intensifies. This makes it almost impossible to give a general outline of the topic “Lermontov and Soviet Poetry,” especially considering the heterogeneity of this influence. On the other hand, it is difficult to name a major poet who does not have a connection with Lermontov’s poetry.

In Mayakovsky, with his radical poetic innovation and focus on the conversational element, we see the “Lermontov” desire for maximum directness and intensity of poetic expression. It seems that Tsvetaeva’s lyrical expressive rhetoric has a Lermontovian nature, which is also noticeable in a less obvious form in Pasternak.

On the other hand, the visible imagery of Yesenin’s landscapes also makes us recall vivid and concrete pictures of nature in Lermontov’s poetry.

As for Mandelstam, the obvious “discreteness” of poetic experience, the reliance not on the flow of poetry, but on the speech embodiment of “lyrical outbursts,” seems to be most directly related to the fundamental discovery of Lermontov the lyricist, which was discussed above.

Subject

The theme of this work is characteristic of Lermontov’s early work - longing for the homeland, for something that is never destined to come true. The motif of loneliness can also be seen in this poem. Romanticism is characteristic of early Lermontov. Only in this context, the “homeland” is the land of supposed ancestors - Scotland, and in more mature work - only Russia, which the poet sincerely loved.

The lyrical hero longs to turn into a bird and leave the alien land on which he was born and forced to live. He draws images of distant ancestors, Scottish fields and mountains, mentally flying over a distant mysterious country. The main character is a lyrical hero whom the author identifies with himself. He languishes with the desire and impossibility to visit the homeland of his ancestors - Scotland. The lyrical hero is clearly present in the poem, leading the reader with him into an illusory world. The pronoun “I” is used quite often by the author, which does not leave an impersonal effect on the lyrical narrative.

Topics and issues

The theme of the poem “The Beggar” can be explored more widely if you write to the Many-Wise Litrekon in the comments, what is missing in this section?

- The main theme of the poem by M.Yu. Lermontov's "The Beggar" is a theme of deception and betrayal

. The main thing here is love deception. The beloved rejects the feelings of the lyrical hero, despite the fact that her love is important to him, like a piece of bread for a hungry beggar. His pleas are unanswered. - Unrequited love

is another theme of the poem. The hero suffers from a lack of reciprocity, and this feeling is equal in strength to hunger. This is a spiritual thirst that cannot be quenched. - Romantic motifs

become pervasive in Lermontov’s work. The main one is loneliness. The lyrical hero is an outcast whom no one values. They don’t understand him, but they already despise him. - The problems in the poem “The Beggar”

are human coldness, callousness and revenge. Instead of the necessary help, the needy receives a stone. Being in distress, he is subjected to even greater suffering and deception. The same event can be a small prank for one and a tragedy for another. The saddest thing is that people convey their feelings to others. The beggar was treated cruelly. After what happened, perhaps he will use this stone to get a piece of bread by force. Once upon a time, Lermontov himself did not receive love from Ekaterina Sushkova, and subsequently their relationship ended in revenge on his part.

Brief Analysis

Before reading this analysis, we recommend that you familiarize yourself with the poem Desire.

History of creation - the poem was written by young Lermontov in 1831. The poet’s passion for the history of his family and the influence of Byron’s traditions played a role in the creation of the elegy “Desire.”

The theme is longing for the homeland, about impossible, unfulfilled dreams, loneliness.

The composition is the reflections of the lyrical hero, his imaginary journey to the country of his ancestors. It consists of 6 stanzas, divided meaningfully into “journey” and “monologue of the lyrical hero.”

Genre : elegy.

Poetic meter - the work is written in alternating amphibrachium and anapest, paired rhyme (AABB).

Epithets - “foggy mountains”, “forgotten dust”, “rusty sword”, “brave fighters”, “alien snow”.

Metaphor – “the waves of the seas spread out.”