“WHAT IS RASKOLNIKOV’S INTERNAL CONTRADITION?”

In world literature, Dostoevsky has the honor of discovering the inexhaustibility and multidimensionality of the human soul. The writer showed the possibility of combining low and high, insignificant and great, vile and noble in one person. Man is a mystery, especially Russian man. “Russian people are generally broad people... broad, like their land, and extremely prone to the fanatical, to the disorderly; but the trouble is to be broad without special genius,” says Svidrigailov. The words of Arkady Ivanovich contain the key to understanding Raskolnikov’s character. The very name of the hero indicates duality, the internal ambiguity of the image. Now let’s listen to the characterization that Razumikhin gives to Rodion Romanovich: “I’ve known Rodion for a year and a half: he’s gloomy, gloomy, arrogant and proud; lately... he’s suspicious and a hypochondriac... Sometimes, however, he’s not a hypochondriac at all, but simply cold and insensitive to the point of inhumanity, really, as if there are two opposite characters in him, alternately... he values himself terribly highly and, it seems, not without some right to do so " The painful internal struggle does not subside for a minute in Raskolnikov. Rodion Romanovich is tormented not by a primitive question - to kill or not to kill, but by an all-encompassing problem: “Is a person a scoundrel, the entire race, that is, the human race.” Marmeladov's story about the greatness of Sonya's sacrifice, his mother's letter about Dunechka's fate, the dream about Savraska - all this flows into the general stream of consciousness of the hero. A meeting with Lizaveta, memories of a recent conversation in a tavern between a student and an officer about the murder of an old pawnbroker lead Raskolnikov to a fatal decision for him.

Dostoevsky's attention is focused on understanding the root causes of Raskolnikov's crime. The words “kill” and “rob” can lead the reader’s thoughts down the wrong path. The point is that Raskolnikov does not kill at all in order to rob. And not at all because he lives in poverty, because “the environment is stuck.” Couldn't he, without waiting for money from his mother and sister, provide for himself financially, as Razumikhin did? Dostoevsky's man is initially free and makes his own choice. This fully applies to Raskolnikov. Murder is the result of free choice. However, the path to “blood according to conscience” is quite complex and lengthy. Raskolnikov's crime includes the creation of the arithmetic theory of the “right to blood.” The internal tragedy and inconsistency of the image lies precisely in the creation of this logically almost invulnerable theory. The “great idea” itself is a response to the crisis state of the world. Raskolnikov is by no means a unique phenomenon. Many people express similar thoughts in the novel: the student in the tavern, Svidrigailov, even Luzhin...

The hero sets out the main provisions of his inhuman theory in confessions to Sonya, in conversations with Porfiry Petrovich, and before that, in hints - in a newspaper article. Rodion Romanovich comments: “... an extraordinary person has the right... to allow his conscience to step over... other obstacles, and only if the fulfillment of his idea (sometimes saving for all mankind) requires it... People, according to the law of nature, are divided in general , into two categories: the lowest (ordinary)… and the people themselves...” Raskolnikov, as we see, substantiates his idea with reference to the good of all humanity, calculated arithmetically. But can the happiness of all mankind be based on blood, on crime? However, the reasoning of the hero, who dreams of “freedom and power... over all trembling creatures,” is not without egoism. “Here’s what: I wanted to become Napoleon, that’s why I killed him,” Raskolnikov admits. “You walked away from God, and God struck you down and handed you over to the devil!” - Sonya says with horror.

The moral and psychological consequences of the crime are exactly the opposite of those that Raskolnikov expected. Basic human connections are falling apart. The hero admits to himself: “Mother, sister, how I loved them! Why do I hate them now? Yes, I hate them, I physically hate them, I can’t stand being around me...” At the same time, Rodion Romanovich decisively overestimates the scale of his own personality: “The old woman is nonsense!.. The old woman was only an illness... I wanted to get over it as quickly as possible... I didn’t kill a person, I killed a principle! I killed the principle, but I didn’t step over it, I stayed on this side... Eh, aesthetically I’m a louse, and nothing else!” Note that Raskolnikov does not abandon theory in general, he only denies himself the right to kill, he only removes himself from the category of “extraordinary people.”

Individualistic theory is the source of the hero’s constant suffering, the source of undying internal struggle. There is no consistent logical refutation of Raskolnikov’s “idea-feelings” in the novel. And is it even possible? And yet, Raskolnikov’s theory has a number of vulnerabilities: how to distinguish between ordinary and extraordinary people; what will happen if everyone thinks they are Napoleons? The inconsistency of the theory is also revealed in contact with “real reality”. The future cannot be predicted arithmetically. The very “arithmetic” that the unfamiliar student spoke about in the tavern suffers a complete collapse. In Raskolnikov's dream about killing an old woman, the blows of the ax do not reach their target. “He... quietly released the ax from the noose and hit the old woman on the crown, once and twice. But it’s strange: she didn’t even move from the blows, like a piece of wood... The old woman sat and laughed...” Raskolnikov’s powerlessness, the lack of control of those around him to his will is expressed by complex figurative symbolism. The world is far from being solved yet, it cannot be solved, the usual cause-and-effect relationships are absent. “A huge, round, copper-red moon looked straight out the window.” “It’s been so quiet for a month,” thought Raskolnikov, “he’s probably asking a riddle now.” Thus, the theory is not refuted, but is, as it were, forced out of the hero’s consciousness and subconscious. The essence of Raskolnikov’s spiritual resurrection lies in the acquisition of “living life”, love, and faith in God through suffering. A dangerous dream about a pestilence marks a way out of the darkness of the labyrinth. The gap between the hero and ordinary convicts is narrowing, and the horizons of the hero’s personality are expanding.

Let's summarize some results. Raskolnikov’s internal tragedy is associated with the hero’s separation from people and with the creation of the inhuman theory of “blood according to conscience.” In his actions, a person is free and independent of social circumstances. The ongoing internal struggle indicates that in Rodion Romanovich, a martyr’s dream to save people from suffering and selfish confidence in his own right to “step over other obstacles” in order to “become Napoleon” simultaneously coexist. At the end of the novel, Raskolnikov comes to spiritual resurrection not as a result of renouncing an idea, but through suffering, faith and love. The Gospel parable about the resurrection of Lazarus is intricately refracted in the destinies of Sonya and Raskolnikov. “They were resurrected by love, the heart of one contained endless sources of life in the heart of the other.” In the epilogue, the writer leaves the heroes on the threshold of a new, unknown life. The prospect of endless spiritual development opens up before Raskolnikov. This demonstrates the humanist writer’s faith in a person—even in a murderer! — the belief that humanity has not yet said its most important word. Everything is ahead!

Collection of ideal social studies essays

All people are contradictory by nature: in each of us such qualities as mercy and cruelty, kindness and heartlessness coexist. F.M. Dostoevsky, a world-famous writer-psychologist, in his work “Crime and Punishment” created the image of a contradictory hero, who at the same time has good nature and misanthropy, the ability to compassion and selfishness... Let us turn to the analysis of the novel to understand what explains the internal inconsistency character.

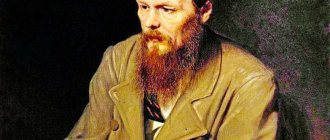

The hero’s surname already indicates his internal split, disunity, and lack of integrity. The exhibition presents a portrait of a former student Raskolnikov: he is a young man of pleasant appearance with delicate features. He was dressed in rags, in which a decent person would be ashamed to go out into the street, on his head was an old red hat, full of holes and frayed. Raskolnikov was not worried about how others saw him. His modest home resembled a coffin: it was a small, miserable closet with low ceilings. The author pays great attention to the interior and landscape to show the reader in what irritable state, “similar to hypochondria,” the main character was in. He was crushed by poverty and was in spiritual exhaustion.

An internal struggle was taking place in the hero’s soul: environment, selfishness, social injustice and partly poverty strangled the generous, educated person in him. Raskolnikov becomes obsessed with the "Napoleonic" theory that there are "extraordinary" people who have the right to sacrifice the lives of other people for the common good. But murder in the name of helping humanity cannot be justified: the scales will definitely tip in one direction.

Following the theory, the student asks himself who he is: “those with the right” or “a trembling creature.” To answer this, Raskolnikov decides to commit the murder of the old pawnbroker, who, being a “louse” herself, decides the fates of many people who turn to her. The theory is doomed to fail. Let us remember the psychological state of the hero before and after the murder. The struggle in his soul brought him to a frenzy, a feverish state. His whole being was opposed to theory. To show this, the author uses various elements of psychologism: a system of doubles (the characters Svidrigailov and Luzhin represent an extreme form of self-affirmation), speech characteristics (internal mon