- Summary

- Nabokov

- Invitation to execution

The work belongs to the surreal literary genre and presents a man named Cincinnatus as the main character of the novel.

The hero finds himself sentenced to death, and this decision is announced to him in accordance with the rules of the country in a whisper in his ear, accompanied by the smiles of the people around him.

Cincinnatus is placed again in the prison fortress under the supervision of the jailer Rodion, who always confuses the keys to the cells.

Returning to the premises, Cincinnatus discovers a lawyer in the cells, deep in thought, but suddenly stood up when the prisoner appeared. Cincinnatus does not want to communicate with the defender, demanding to leave the cell.

Then the suicide bomber discovers a snow-white sheet lying on it, on which is written a phrase about Cincinnatus’ premonition of life’s ending. After reading the text, the hero becomes aware of some kind of observation of his person. Cincinnatus's hand crosses out the written words and rolls the sheet into a ram's horn.

After a while, the prisoner is visited by the head of the prison, who in a friendly manner promises Cincinnatus to improve the conditions of his cell detention, as well as to diversify his diet. The prisoner is interested in the date of the execution, but his question remains unanswered.

Remembering his past life, moments of his childhood float before Cincinnatus’s eyes, in which the boy learns to hide his own unusualness, inherited from his father, from those around him. The child enjoys reading ancient books and also learns how to make dolls, which he later gives away to people.

Having matured, Cincinnatus gets a job as a teacher working with mentally retarded children. While working in a doll shop, he meets his future wife Marfinka. However, marital relations are subsequently not cloudless, since the wife enters into an extramarital affair, from which she has two children. The son is lame and angry, and the daughter turns out to be blind. After some time, both children find themselves under the care of Cincinnatus.

Taking a break from his memories, the hero again makes attempts to find out the date of his own execution, but neither the lawyer nor the prison warden’s daughter Emmochka, who is visiting him, informs him about this.

The next day begins with a visit from the prison warden, who tells Cincinnatus two pieces of news, the first of which concerns the meeting he is allowed with his wife, and the second reports the appearance of a cell neighbor named Monsieur Pierre, an obsessive man who pesters Cincinnatus with his photographs and card tricks.

During a date, not only his wife comes to Cincinnatus, but also the whole family, as well as Marfinka’s new boyfriend. The date takes place against the backdrop of constant abuse from his father-in-law and jokes from other family members regarding Cincinnatus, so he is unable to communicate with his wife on an important topic.

For several nights in a row, Cincinnatus hears strange sounds, vaguely reminiscent of mining work. One day, the wall of the cell is destroyed and the hero’s cell neighbor appears in the opening. The prisoners leave the prison and Cincinnatus, together with Monsieur Pierre, get to the prison warden's apartment, accompanied by Emmie. Here, a death row inmate learns about the friendship between the prison warden and his former cellmate.

Soon the date for the hero’s execution is set, and the executioner is also determined, who becomes Monsieur Pierre. At the moment of execution of the sentence, Cincinnatus refuses the executioner and exposes himself to death on his own. However, in the hero’s own mind, it seems that he is leaving the place of execution, rising into the air.

The novel, written in an unusual textual manner, demonstrates the impossibility of putting a creative personality into the generally accepted framework of life.

Reader's diary.

Other works by the author: ← Mashenka↑ NabokovaDar →

Invitation to execution

“In accordance with the law, Cincinnatus Ts.’s death sentence was announced in a whisper.” The unforgivable fault of Cincinnatus is his “impenetrability”, “opacity” for the others, who are terribly similar (the jailer Rodion every now and then turns into the director of the prison, Rodrigue Ivanovich, and vice versa; the lawyer and the prosecutor by law must be half-brothers, but if this does not work out to pick them up - they are made up so that they look alike), “souls transparent to each other.” This feature has been inherent in Cincinnatus since childhood (inherited from his father, as his mother, Cecilia Ts., who came to visit the prison, tells him, puny, curious, in an oilcloth waterproof and with an obstetric bag), but for some time he manages to hide his difference from the others . Cincinnatus begins to work, and in the evenings he revels in old books, becoming addicted to the mythical 19th century. Moreover, he is engaged in making soft dolls for schoolgirls: “there was little hairy Pushkin in a bekesh, and a rat-like Gogol in a flowery vest, and old Tolstoy, thick-nosed, in a zipun, and many others.” Here, in the workshop, Cincinnatus meets Marfinka, whom he marries when he turns twenty-two and is transferred to a kindergarten as a teacher. In the first year of marriage, Marfinka begins to cheat on him. She will have children, a boy and a girl, not from Cincinnatus. The boy is lame and angry, the fat girl is almost blind. Ironically, both children end up in the care of Cincinnatus (he is entrusted with “lame, hunchbacked, squinty” children in the garden). Cincinnatus stops taking care of himself, and his “opacity” becomes noticeable to others. So he finds himself imprisoned in a fortress.

Continued after advertisement:

After hearing the verdict, Cincinnatus tries to find out when the execution is scheduled, but the jailers do not tell him. Cincinnatus is taken out to look at the city from the fortress tower. Twelve-year-old Emmochka, the daughter of the prison director, suddenly seems to Cincinnatus as the embodiment of the promise of escape... The prisoner whiles away the time by looking at magazines. He makes notes, trying to comprehend his own life, his individuality: “I am not simple... I am the one who is alive among you... Not only are my eyes different, and my hearing, and my taste, - not only my sense of smell, like that of a deer, but my sense of touch, like that of bat, - but most importantly: the gift of combining all this at one point ... "

Another prisoner appears in the fortress, a beardless, fat man of about thirty. Neat prison pajamas, morocco shoes, blond hair parted in the middle, wonderful, even teeth whitening between her crimson lips.

The meeting with Marfinka promised to Cincinnatus is postponed (according to the law, the meeting is allowed only after a week after the trial). The director of the prison in a solemn manner (on the table there is a tablecloth and a vase with cheeky peonies) introduces Cincinnatus to his neighbor - M'sieur Pierre. Monsieur Pierre, who visited Cincinnatus in his cell, tries to entertain him with amateur photographs, most of which depict himself, card tricks, and anecdotes. But Cincinnatus, to the offense and dissatisfaction of Rodrigue Ivanovich, is closed and unfriendly.

Briefly exists thanks to advertising:

The next day, not only Marfinka, but also her entire family (father, twin brothers, grandparents - “so old that they were already visible”, children) and, finally, a young man with an impeccable profile - the current Marfinka's gentleman. Furniture, household utensils, and individual wall parts also arrive. Cincinnatus is unable to say a word alone with Marfinka. His father-in-law never ceases to reproach him, his brother-in-law persuades him to repent (“Think how unpleasant it is when your head is chopped off”), the young man begs Marfinka to put on a shawl. Then, having collected their things (the furniture is carried out by porters), everyone leaves.

While awaiting execution, Cincinnatus feels even more acutely his difference from everyone else. In this world, where “matter is tired: time sweetly slumbered,” only a small part of Cincinnatus wanders, perplexed, in the imaginary world, and the main part of it is located in a completely different place. But even so, his real life “comes through too much,” causing rejection and protest from those around him. Cincinnatus returns to the interrupted reading. The famous novel he reads has the Latin title “Quercus” (“Oak”) and is a biography of a tree. The author talks about those historical events (or shadows of events) that the oak tree could have witnessed: now this is a dialogue of warriors, now a resting place of robbers, now the flight of a nobleman from the royal wrath... In the intervals between these events, the oak tree is considered from the point of view of dendrology, ornithology and other sciences , provides a detailed list of all monograms on the bark with their interpretation. Much attention is paid to the music of the waters, the palette of dawns and the behavior of the weather. This, undoubtedly, is the best of what was created by Cincinnatus’s time, nevertheless it seems to him distant, false, dead.

Continued after advertisement:

Exhausted by waiting for the executioner to arrive, waiting for the execution, Cincinnatus falls asleep. Suddenly he is awakened by tapping, some scraping sounds, clearly audible in the silence of the night. Judging by the sounds, this is a tunnel. Until the morning Cincinnatus listens to them.

At night the sounds resume, and day after day M’sieur Pierre appears to Cincinnatus with vulgar conversations. The yellow wall cracks, opens up with a roar, and M’sieur Pierre and Rodrigue Ivanovich crawl out of the black hole, choking with laughter. M'sieur Pierre invites Cincinnatus to visit him, and he, seeing no other possibility, crawls along the aisle ahead of M'sieur Pierre into his cell. M'sieur Pierre expresses joy at his newly established friendship with Cincinnatus - this was his first task. Then M'sieur Pierre unlocks a large case standing in the corner with a key, in which there is a wide ax.

Cincinnatus climbs back along the dug passage, but suddenly finds himself in a cave, and then through a crack in the rock he gets out into freedom. He sees a smoky, blue city with windows like hot coals, and hurries down. Emmochka appears from behind the ledge of the wall and leads him along. Through a small door in the wall they find themselves in a darkish corridor and find themselves in the director’s apartment, where the family of Rodrigue Ivanovich and M’sieur Pierre are drinking tea at an oval table in the dining room.

Briefly exists thanks to advertising:

As is customary, on the eve of the execution, M'sieur Pierre and Cincinnatus pay a visit to all the main officials. A sumptuous dinner was held in their honor, and the garden was illuminated with the monogram “P” and “C” (not quite published, however). M'sieur Pierre, as usual, is the center of attention, while Cincinnatus is silent and absent-minded.

In the morning, Marfinka comes to Cincinnatus, complaining that it was difficult to get permission (“Of course, I had to make a small concession—in a word, the usual story”). Marfinka talks about her date with Cincinnatus’s mother, that her neighbor is wooing her, and ingenuously offers herself to Cincinnatus (“Leave me alone. What nonsense,” says Cincinnatus). Martha is attracted by a finger stuck through the slightly opened door, she disappears for three quarters of an hour, and Cincinnatus, during her absence, thinks that not only has he not begun an urgent, important conversation with her, but now he cannot even express this important thing. Marfinka, disappointed with the date, leaves Cincinnatus (“I was ready to give you everything. It was worth trying”).

Cincinnatus sits down to write: “This is the dead end of life here, and it is not within its narrow confines to seek salvation.” M'sieur Pierre and her two henchmen appear, in whom it is almost impossible to recognize the lawyer and director of the prison. A bay nag drags a peeling stroller with them down into the city. Having heard about the execution, the public begins to gather. The scarlet platform of the scaffold rises in the square. Cincinnatus, so that no one touches him, has to almost run to the platform. While preparations are underway, he looks around: something has happened to the lighting, the sun is not doing well, and part of the sky is shaking. One after another, the poplars that line the square fall.

Advertising:

Cincinnatus himself takes off his shirt and lies down on the block. He begins to count: “one Cincinnatus was counting, and the other Cincinnatus had already stopped listening to the receding ringing of an unnecessary count, stood up and looked around.” The executioner has not yet completely stopped, but the railing is visible through his torso. The audience is completely transparent.

Cincinnatus slowly descends and walks along the unsteady debris. Behind him the platform collapses. The much smaller Rodrigue unsuccessfully tries to stop Cincinnatus. A woman in a black shawl carries a small executioner in her arms. Everything spreads and falls, and Cincinnatus walks among the dust and fallen things in the direction where, judging by the voices, people like him are standing.

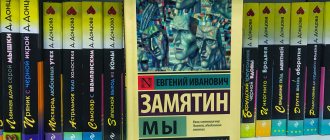

Vladimir Nabokov "Invitation to Execution"

It’s not very often that you get great pleasure directly from the reading process itself, when every paragraph, every line, sometimes even a single word appears as something complete and valuable in its own right. “Invitation to Execution” is a vivid example of what, generally speaking, a true creation of literature, called the “Russian novel,” should be. (It seems to me that Nabokov wrote his best works in Russian. And expressions like “Cut down, Socratic” are only possible in Russian.) This is a deeply original, both in content and in language, work of the master, which, It goes without saying that it is not subject to unambiguous and easy interpretation. Perhaps it is as “opaque” for this purpose as its main character, Cincinnatus T, is opaque for the inhabitants of his strange world. We can only talk about the associations with which such reading is so rich.

The theme of the hero's painful wait for execution is found in the works of many outstanding writers. It is enough to recall the famous works of V. Hugo and L. Andreev. Formally, it is also present in Nabokov, but in a form weakened, one might say, by surrealism, phantasmagoria and the growing atmosphere of the absurd. Although, thanks to his writing talent, this absurdity acquires, as they say, frightening features of reality. But perhaps, more than the fear of death, Cincinnatus is tormented by the consciousness of his initial helplessness and doom. In fact, he himself is one suffering consciousness, an absolutely passive figure, meekly accepting his fate and only trying to maintain his dignity. Cincinnatus's passivity seems to be even emphasized by the fragility of his figure. Complete, transcendental and fantastic loneliness, a loneliness that is difficult to imagine, dominates him. Melancholy, what melancholy, he repeats every now and then. Everyone around, starting with Marthene and ending with the “friendly” executioner Monsieur Pierre, subjects Cincinnatus to subtle bullying, without even the slightest degree realizing it, without having any goal-setting for it. By the way, this Monsieur Pierre, this “maestro” and favorite of women with false jaws, is a figure as repulsive as he is unforgettable in his absurd monstrosity. Surprisingly, the characters in the novel, except for Cincinnatus, constantly balance on the elusive line between reality and props. The props in this case are not physical (like the dolls that come to life in M.E. Saltykov-Shchedrin’s story “Toy Craftsmen”), although in the end it also appears, but it is spiritual. “Why, in fact, is everything arranged this way and not otherwise?” - I would like to ask Cincinnata, but there is no one to ask, because even God is absent from his world. His “gnoseological vileness” is an unspoken and not fully realized ontological protest directed to the whole world. It seems that it was not easy to invent and recreate (on paper) such an “inferno”. And with a strange feeling you recognize Russian, Russian features in this picture. It is interesting that a similar feeling of acute melancholy, of the “wrongness” of life arose in me, at one time, when reading a work of a completely different type. Namely, “Children of the Dungeon” by V.G. Korolenko, where the decline and death of a beggar girl is shown through the eyes of a half-child, half-teenager.

From the first line, the text commandingly attracts attention with its semantic richness and artistic perfection. Once having set foot on the path of this novel, universal in genre and style, the reader is simply forced to follow it to the end. As for the ending, it probably fundamentally, as a poetic image, cannot be subjected to a purely rational interpretation. Many interpretations are possible (see, for example, N. Bux “Scaffold in the Crystal Palace”). By the way, “sideways studies” are akin to “Homeric studies” in their scope and richness. But a comprehensive and cold analysis of texts, no matter how interesting it may be, lies somewhat aside from the direct, personal perception of a work of art (literature). Nabokov’s words are well known: “Great novels are, first of all, magnificent fairy tales... Literature does not tell the truth, but invents it.” The thought flashed through my mind of a rebirth similar to that experienced by Athanasius Pernath in Mayrink’s “The Golem.” In any case, even the most painful and absurd nightmare has an end and this can be seen as a symbol of hope.